Japanese art with a mysterious edge

Back in 2016, I wandered into the Fantastique exhibition at the Petit Palais in Paris, a dream for anyone who loves their art with a hint of the bizarre. The lineup was stellar: Goya, Redon, Delacroix, Gustave Doré… names that already lived rent-free in my mind and I naturally couldn’t resist the chance to see their engravings and lithographs in person. But among the 170+ works, one name caught me by surprise: Kuniyoshi.

Already a lover of Japanese craftsmanship, porcelain, bonsai, traditional tattoos, the meditative elegance of kimonos, and their philosophies intertwined in their culture, it was no surprise I fell for Kuniyoshi. He masterfully combined the beauty of traditional Japanese art with a darker side that I’ve always felt drawned to.

The Ukiyo-e style of Utagawa Kuniyoshi

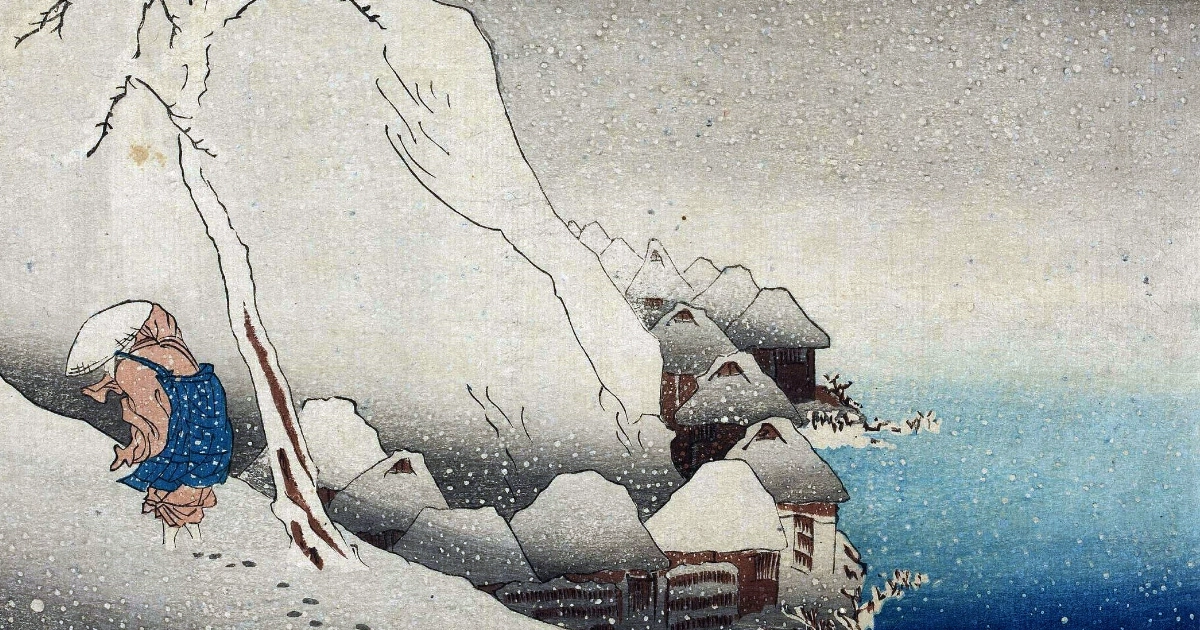

Most people think of Hokusai or Utamaro when they hear “ukiyo-e.” Fair enough—they’re brilliant. But Kuniyoshi? He was the misfit in the room. Less pretty. More guts. And probably one of the boldest visual storytellers Japan has ever produced. This only deepens my appreciation for his work, as I’m often drawn to rebellious spirits.

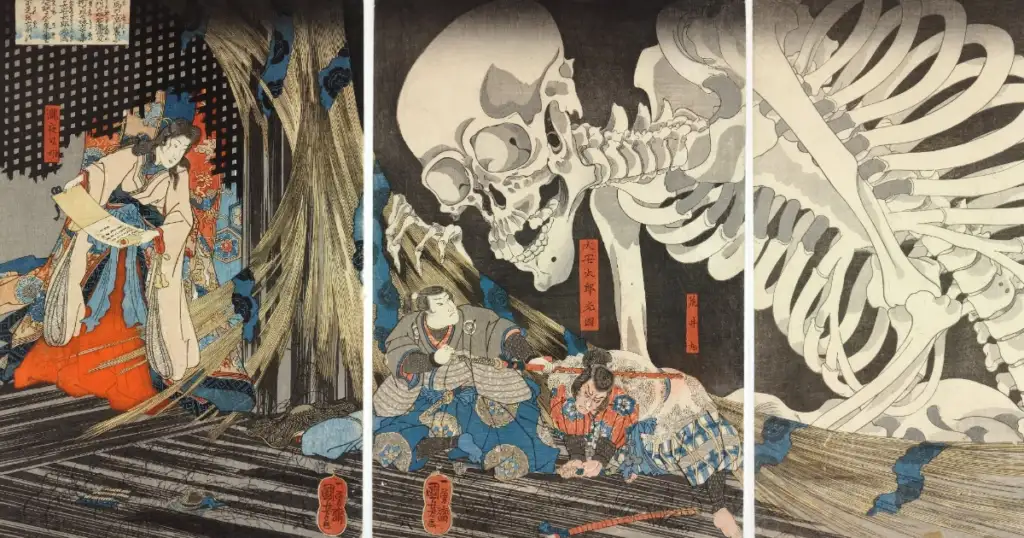

His nonconformist approach set him apart from the decorative Japonism that swept through Europe in the late 19th century, even though he was admired by icons like Monet and Rodin. His prints stand out for their originality and bold framing, characterized by violent depictions of monsters and warriors, humor in shadow play, caricatures, and intricate representations of cats. Kuniyoshi’s graphic style continues to influence both the tattoo world and contemporary manga, making his work all the more fascinating.

Born to create

Kuniyoshi was born in Edo (what we now call Tokyo) in 1797, the son of a silk dyer. You can imagine the early influence, colour, textiles, fluid patterns. He helped his father design fabric as a child, which no doubt shaped his eye for detail and composition. At just 14, he joined the Utagawa school, run by the ukiyo-e master Toyokuni, who gave him the artist name “Utagawa Kuniyoshi.” He wasn’t just drawing for fun, he was building a visual legacy. And what a legacy: nearly 10,000 prints over his lifetime.

Rebels, outlaws, and coded resistance

By 1827, Edo was under the suffocating grip of government censorship. Artists were expected to stay within the lines, literally. But Kuniyoshi, true to form, refused to be boxed in. He released The 108 Heroes of the Tale of Suikoden, a wildly popular series based on a 14th-century Chinese novel, this series depicted the adventures of 108 rebels and heroic bandits, resonating deeply with the oppressed Edo population. Think heavily tattooed bandits and warriors, all with a strong sense of justice. It struck a nerve with the people longing for voices of defiance and bravery in a time of repression.

When censorship tightened even more in the 1840s, banning depictions of kabuki actors and courtesans (frequent themes in Kuniyoshi’s prints), Kuniyoshi didn’t back down. Instead, he got clever. He started using humanlike animals to get around the rules, satire cloaked in symbolism. You’d see frogs dressed as samurai, cats playing at politics. The humour was sharp, and the message clear to anyone paying attention.

As his politically charged works drew the scrutiny of the authorities, it did lead to the surveillance and close monitoring of his activities. While he was never imprisoned or formally punished, the restrictions imposed by the Tokugawa shogunate (which was a military government let by a military leader called shogun) did present significant obstacles.

That level of inventiveness? It’s genius. And it only made me admire him more.

From taboo to trend: Kuniyoshi and tattoo culture

One of my favourite things about Kuniyoshi is how his art leapt off the page and onto skin. His rebellious heroes inspired a tattoo craze, intricate body suits featuring fierce animals and warriors became all the rage.

It’s wild to think about, considering tattoos in Japan once were a form of punishment for criminals. But through Kuniyoshi’s prints, they were reimagined as a form of storytelling, of identity, of power. You can still see his influence in modern irezumi (traditional Japanese tattooing) today.

The woodblock printing process (aka patience personified)

Let’s take a moment to appreciate the process behind these prints. Woodblock printing arrived in Japan from China around the 8th century and was originally used to reproduce sacred Buddhist texts. Fast forward to the Edo period, and it became a form of mass media, books, posters, and art, all carved and printed by hand. Publishers began using this technique to produce affordable literature and art, tapping into the growing demand for both. They created not only illustrated books but also standalone images, frequently enlisting famous artists -like Kuniyoshi- to design these prints.

Videos of the craft of wood carving are hard to find. But if you’re interested, there is a British/Canadian woodblock printer and carver on YouTube who recorded every step of this meticulous art.

You have to be made out of a very particular type of wood to be a carver (pun intended). Crafting these intricate designs into wood requires an extraordinary level of skill and patience. Watching David Bull’s video, I’m amazed by the contrast between his seemingly large hands and the tiny slivers of wood he meticulously carves. His use of a microscope to capture the finest brush strokes of the original drawing highlights the incredible attention to detail required.

Many Ukiyo-e prints involve multiple colors, each requiring a separate woodblock, making the creation process span several months or longer depending on the size of the print. The result is visually stunning but also a testament to the time and dedication invested. It’s this meticulous effort and the lengthy process that make each print truly special. One thing’s for sure, I couldn’t manage it, could you?

Dramatic compositions

Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s dynamic and dramatic compositions truly set him apart in the ukiyo-e tradition. His artistic style evolved significantly throughout his career, especially during the 1830s when his work became notably more bold and expressive. This was the period when his his style became more bold and expressive.

Kuniyoshi was a master at capturing movement, often depicting characters in mid-action with flowing garments, wind-swept hair, and exaggerated poses. His prints convey a sense of immediacy and tension, making it feel as though the scene is unfolding right before your eyes. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Kuniyoshi experimented with perspective, using dramatic angles, foreshortening, and overlapping figures to create depth and enhance the action. His characters were brought to life with intense facial expressions, conveying emotions that range from rage and determination to fear and sorrow, adding a profound emotional depth to his work. I can only imagine the incredible skill required to woodcarve such intricate sentiments.

Kuniyoshi ‘s feline friends

Cats hold a special place in Japanese culture, credited with protecting the earliest Buddhist scriptures brought to Japan by safeguarding them from mice during their voyage on ships. These feline guardians carry various cultural meanings, some, like the maneki-neko, are symbols of good luck and fortune, while others, such as the bakeneko, are yōkai, supernatural entities featured in Japanese legends. Beyond their mystical roles, the independent and graceful nature of cats resonates deeply with traditional Japanese values and aesthetics.

Kuniyoshi, like many Japanese people (and let’s not forget the man who drew cats Louis Wain), had a deep affection for cats. As his fame grew, he indulged his love for these creatures by frequently including them in his prints. His studio was famously filled with cats. Sometimes one or two. Sometimes ten or more. Visitors often found him drawing with a cat tucked into his kimono, purring away.

His devotion to his feline companions was profound, when one passed away, Kuniyoshi would immediately take it to a nearby Buddhist temple and maintained a Buddhist altar at home, dedicated to the memory of his departed cats. I can’t help but imagine how wonderful it would have been to be one of his feline friends, cherished and surrounded by the beauty of his art.

Conclusion

In essence, Kuniyoshi’s art is a celebration of life, imagination, and resistance. It’s rich in detail, emotion, and meaning, making it a joy to look at but also a rewarding experience to study and understand. Whether you’re drawn to his rebellious mind, his dynamic action scenes, his clever use of symbolism, or his charming depictions of everyday life, Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s work offers something for everyone to love.

If you’re interested in seeing Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s art in person, you have several options around the world where his works are on display, especially in museums with extensive collections of Japanese art. But to immerse yourself in the culture, I recommend going to the The Tokyo National Museum, the Edo Tokyo Museum or the Hokusai Museum.

Or, if you’re not hopping on a plane anytime soon, find a quiet moment and search out his prints online. Let the colours and chaos pull you in. And maybe keep a cat nearby while you look.