If you’ve never heard of Harry Clarke, I envy the experience you’re about to have. Clarke was part mystic, part illustrator, part glassworker, and entirely an artist. And though most people associate his name with Art Nouveau stained glass in Irish chapels, I know him best for something a little darker: his extraordinary etchings for the works of Edgar Allan Poe (and the fairytales of Charles Perrault and Christian Andersen).

Yes, Clarke took Poe’s already chilling tales and spun them into something even more chilling. So if you’re into that dark art, melancholic elegance, you’re in for a treat.

The early years of a gothic mind

Harry Clarke, born in Dublin in 1889, grew up in a family skilled in making stained-glass art. His father, Joshua Clarke, had a thriving glass studio named Joshua Clarke & Sons. From the very beginning, Harry was immersed in a world of vivid colors and shadows. As a teenager, he attended the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art. It was there that he developed a unique artistic style, combining medieval imagery with a powerful modern touch.

Harry drew inspiration from various artistic influences. He admired the intricate lines of Aubrey Beardsley, the decorative patterns of the Arts and Crafts movement, and the mysterious allure of Symbolism. Unlike others who softened these styles, Harry made them more intense and defined. His artwork often suggested mystical or unusual themes. Harry had a strong interest in storytelling through art. His creations were dynamic, filled with emotion, and driven by a desire to expose the darker aspects of the human psyche.

The stained glass legacy

Clarke’s stained glass work seem like they belong to another world. He completed over 160 stained glass windows in churches and institutions throughout Ireland and the UK. Some of his best-known ecclesiastical works include the windows in the Honan Chapel at University College Cork and St. Mary’s Church in Ballinrobe, County Mayo. These windows are surreal visions bathed in cobalt blue and blood red. Saints stare out with elongated limbs and hollow eyes, cloaked in robes patterned with stars, insects, and mystical flora.

What set Clarke apart in this medium was his almost obsessive attention to detail. He would often work alone, preferring to paint the glass himself rather than delegate to studio assistants. His compositions were densely packed and rich in symbolism, often mesmerising in their emotional intensity.

Tales of terror: illustrating Edgar Allan Poe

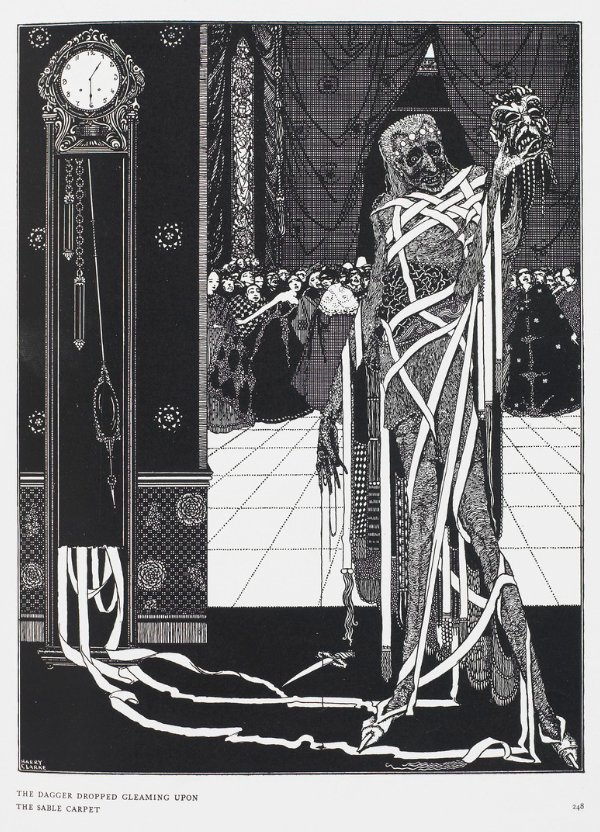

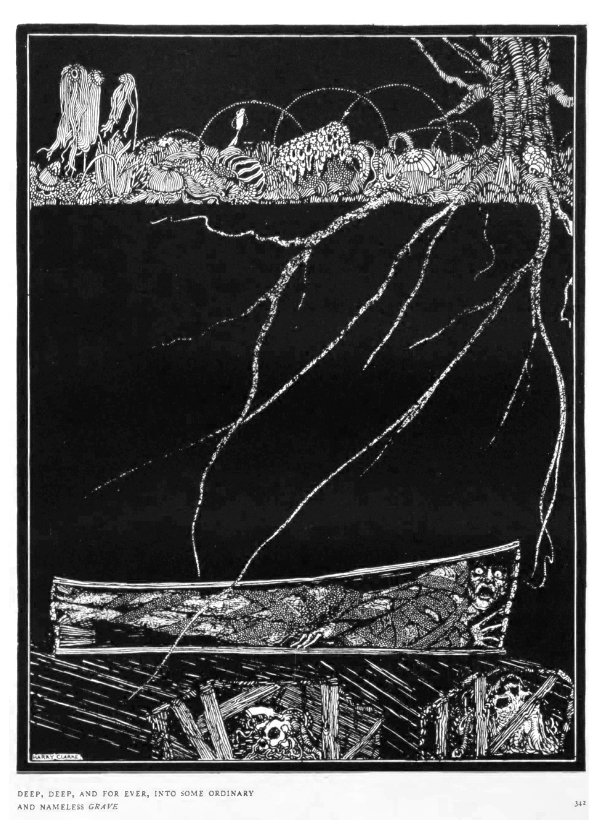

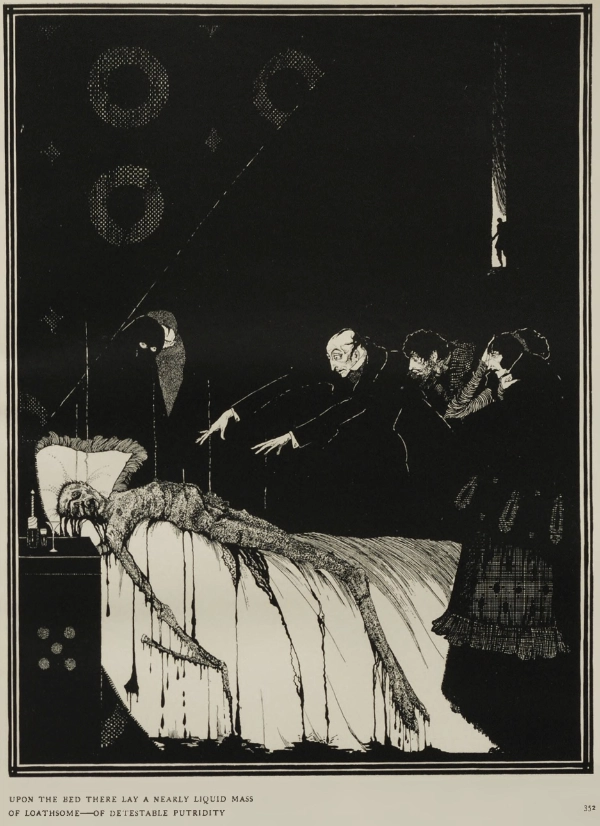

And now, to my favourite part. In 1919, Clarke was commissioned to illustrate a special edition of Edgar Allan Poe’s “Tales of Mystery and Imagination” by George G. Harrap and Co. It was a match made in heaven (or hell?). Poe’s work already dealt with obsession, decay, madness, and the supernatural, themes Clarke had been orbiting for years. What came out from this collaboration were some of the most iconic book illustrations of the 20th century. That’s how I first met Harry Clarke, and I was hooked from the moment I saw that first illustration.

Clarke’s version of “Tales of Mystery and Imagination” included 24 black-and-white illustrations and eight full-colour plates. Every single one is ridiculously detailed, moody, and absolutely loaded with atmosphere. His take on The Masque of the Red Death gets a lot of attention (rightfully so). It’s a full-on sensory overload: heavy baroque flair, masks everywhere, that strange, uneasy lighting, and a claustrophobic tension that drips off the page. But the one that really got under my skin, the one that properly stopped me in my tracks, was his illustration for Poe’s The Premature Burial. That one haunted me. Still does, honestly.

What made Clarke’s illustrations hit so hard was the way he nailed that fever-dream spiral Poe was always weaving, the slow, slinking descent into madness, that pull towards death. All the things I look for in dark art were right there. The raw, unnerving honesty. The truth hiding inside the truth.

Clarke’s dark elegance

There’s always this push and pull in his work, something seductive brushing up against something unsettling. A beautiful woman lounging against a tomb, her hair curling into skulls like it’s no big deal. Or a velvet-draped skeleton gazing straight through you. Clarke understood visual storytelling at a level others don’t. Even when he was working with religious or moral themes, he slipped in his perspectives. Nothing was ever one-note, it always left you lingering and wondering.

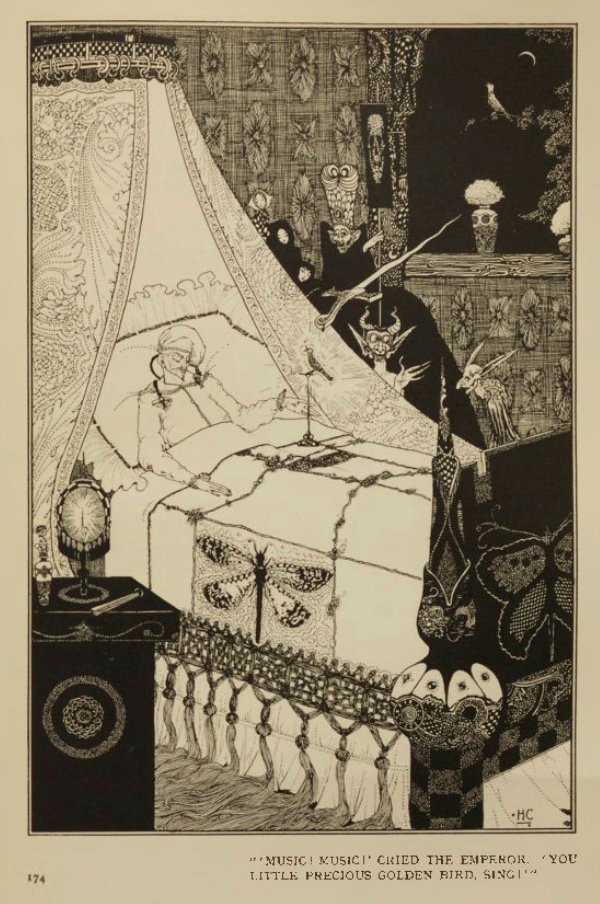

Beyond Poe: Faust, Perrault, and Andersen

In 1925, Clarke also took on Goethe’s Faust, and honestly, some say he outdid himself there. The material was right in his wheelhouse: damnation, temptation, existential dread, it practically begged for Clarke’s brand of beautiful unease. He also brought his dark touch to Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen and Charles Perrault. Forget cosy bedtime stories, he pulled the mask off those stories and revealed something strange and terrifying beneath to stories many people associate with childhood innocence.

Clarke’s “Sleeping Beauty” isn’t pastel fairytale with satin gowns and birdsong like everyone knows it today. It’s heavier and sadder, a kingdom soaked in quiet magic and long sorrow. The sleep doesn’t feel enchanted at all, it actually feels final. Like mourning in slow motion. Same tale, completely different feeling.

Personal life and health decline

Sadly, despite his rising fame, Clarke’s life was marked by chronic illness. He suffered from tuberculosis, which grew steadily worse in his thirties. He made several trips to Switzerland for treatment and was forced to rely more on studio assistants in his final years. Still, he continued to work, his output never losing its strange allure or technical brilliance.

He died in 1931 at the young age of 41, leaving behind a body of work that continues to captivate and unsettle.

Why Harry Clarke still matters

Clarke’s work remains a reminder that detail matters. Every line, every shadow, every shimmering edge of weirdness. He also reminds us that beauty isn’t always light and soft. Sometimes it’s uncomfortable. Sometimes it comes wrapped in bones and candlelight.

And for anyone working in the creative space, he’s a reminder to stop sanding off your edges. He didn’t try to make everyone happy, and built a visual language so distinct, you could spot it from across the room. Clarke’s work proves art doesn’t have to be polite to be powerful. It just needs to be honest. Honest, and a little haunted.

Where to experience Clarke

- Tales of Mystery and Imagination (especially the 1919 and 1923 editions)

- The Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin (for original illustrations and glass)

- Honan Chapel, Cork

- St. Mary’s Church, Ballinrobe

- National Gallery of Ireland

There’s also a fascinating documentary called Darkness in Light: The Art of Harry Clarke, which explores his artistic achievements and his inner world.

Conclusion

Harry Clarke came into my life and I could never not forget his style and illustrations. He was a storyteller, a visionary with a spine of gothic steel. Whether rendering saints or sinners, angels or phantoms, his work invites you to pause, look closer, and get that chill of honesty. It pulls you in and forces you to ask why something that makes you feel a little uneasy can also be so beautiful.