Type 5,607,249 into a search bar and you’ll immediately be redirected to the great Roman Opalka.

Opalka painted a little different from others. He didn’t do it with Munch’s expressionist urgency, or Pollock’s flailing energy, and certainly not in Keith Haring’s bright colours. His approach was slower. More precise. Almost imperceptible. Tiny, white numbers unfolding across canvas like falling grains of rice, steady, deliberate and barely visible.

Roman Opalka before the 60’s

Born in 1931 in France to Polish parents, Opalka’s early years were shaped by migration, upheaval and war. His family returned to Poland before the outbreak of WWII, and in 1940, they were deported to Germany for forced labour. After the war, Opalka trained as a lithographer before studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. By the 1960s, he had begun wrestling with an idea that would consume the rest of his life.

Recording existence

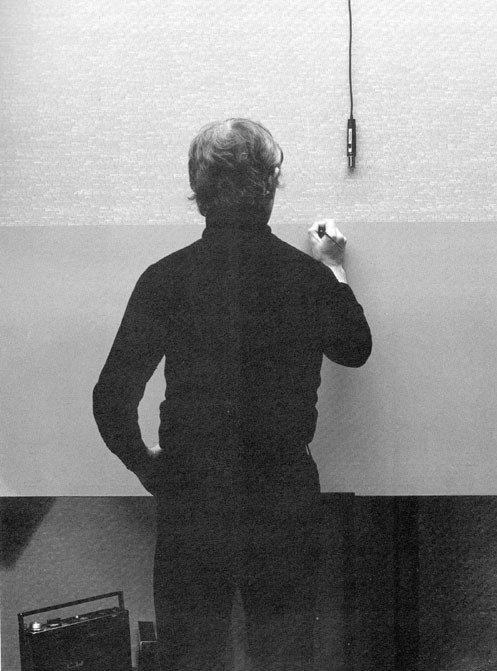

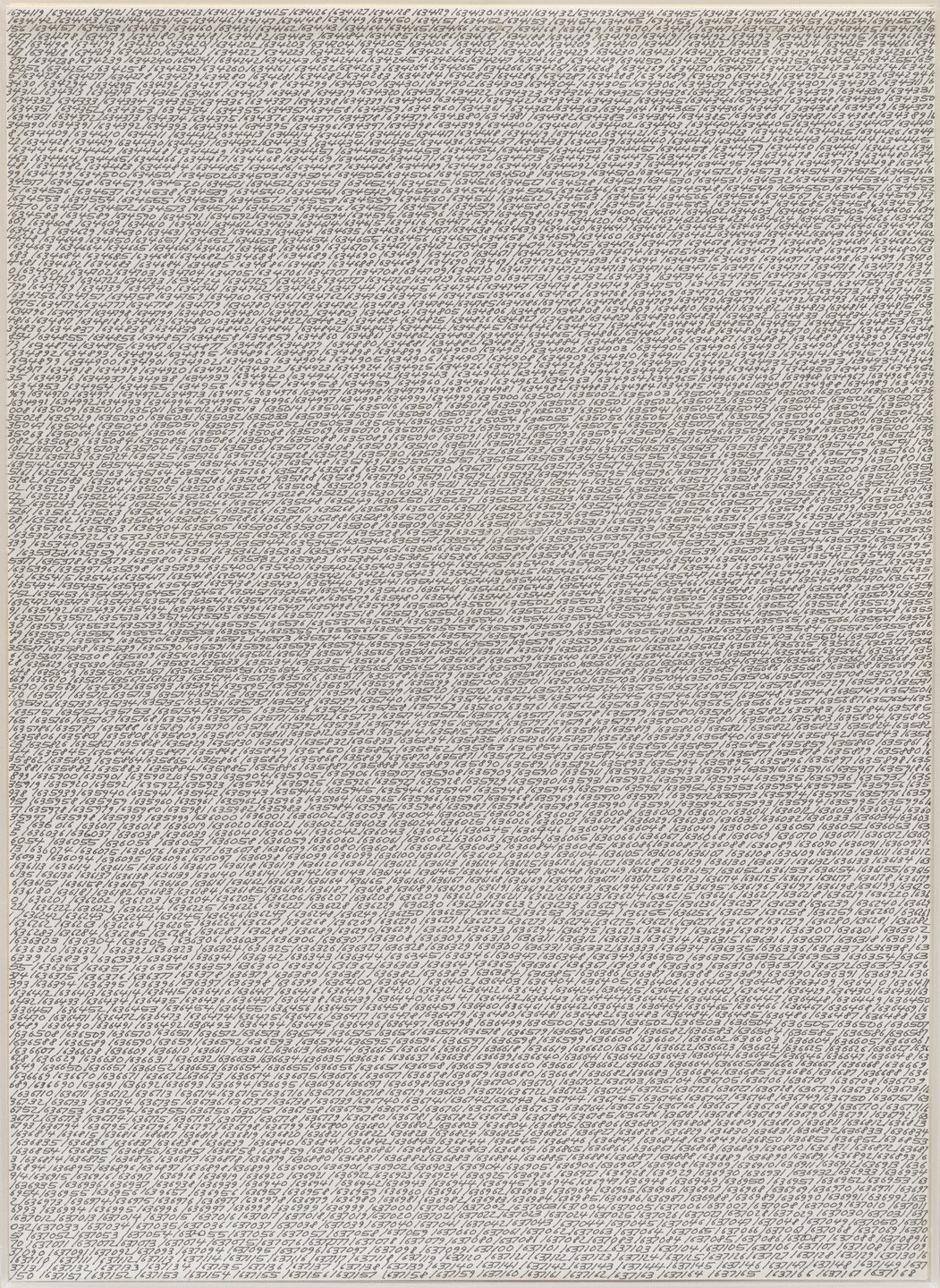

In 1965, while in his studio in Warsaw, Opalka started a project titled “1965 / 1 – ∞”, a philosophical and spiritual image of the progression of time and of life and death. The concept was deceptively simple: to paint numbers from one to infinity, each number following the last, continuing until his death. He began on a black background, hand-painting white digits in horizontal rows. The size of each canvas, or “Detail” as he called them, was fixed: 196 x 135 cm, the dimensions of his studio door! Nothing was arbitrary.

Each canvas began where the last one left off. There was no sketching, no improvisation, just a disciplined progression. And with each new canvas, Opalka added 1% more white to the background. Over time, this created an almost imperceptible shift in tone, so gradual you didn’t see it unless you saw many paintings side by side. By the 2000s, the numbers were barely distinguishable from their backgrounds.

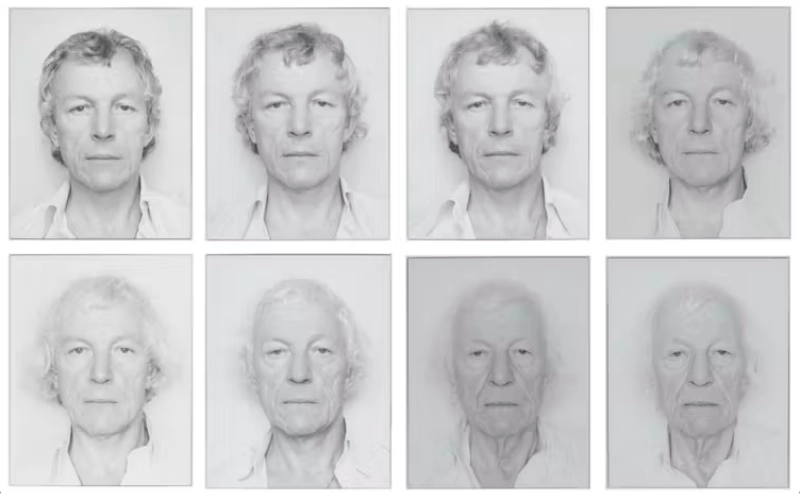

Roman Opalka was staging a performance of duration, recording his own mortality in digits. That’s the part that I find most interesting. If you ask yourself how could you visualise a life, an existence, this is it. On top of that visualisation and alongside the paintings, he began recording himself reading each number aloud in Polish. Every session of painting was paired with this act of vocal documentation, turning numbers into time-stamped breath. From 1972 onwards, he added another element: at the end of each day’s work, he took a black-and-white photograph of his face, always in front of the same neutral background, without expression. What started as a conceptual device became a physical diary of ageing.

Intimate and human

The triad of painted number, spoken number, and photographic self-portrait forms the full structure of Opalka’s work. Conceptually, Opalka was part of a lineage that includes On Kawara, Hanne Darboven, and Tehching Hsieh, all artists whose practices revolve around time, endurance, and documentation. But Opalka’s approach was distinct in its poetic minimalism. While Kawara’s date paintings stamped the now, Opalka’s numbers reached into the infinite future. To the unknowing, the numbers were meaningless abstractions, but to the one who created them, they were everything.

There’s something achingly human in Opalka’s project. Every canvas is a record of days lived, and, if you linger on it a bit longer, also days lost. Each number ticks like a fleeting moment. Over the years, the white paint grows whiter, almost spectral. It reminds me of how people fade with age, less seen, less vibrant, as if dissolving into the background of society. That’s what struck me when I first encountered Roman Opalka’s work. Though, hopefully, that’s not the only way to grow old!

Memento Mori

Over the decades, Opalka’s once-youthful face gradually wore the weight of time. As a woman, I’ll admit, ageing unsettles me. Deep down, I’m grateful to grow older. But physically? I’d rather stay frozen in that ageless space we all secretly wish for. His self-portraits carry such tenderness, but they’re also the sign of erosion. A person slowly aging, frame by frame.

And the truth is, we’re all watching that happen, every day, with everyone around us. People change right in front of our eyes. Their faces shift, hair greys, posture softens. Each day they’re a little closer to the end, and somehow, we don’t really see it. Our minds trick us into thinking they’ll always be there.

That’s what makes Opalka’s work so piercing. It doesn’t just confront time, it records it. It’s hauntingly good. Sad, yes, but also a wake-up call. A reminder to really be here. To live and not waste your time.

We are, and are about not to be

Roman Opalka often spoke of his work as a way of coming to terms with death. “All my work is a single thing,” he said, “the description from number one to infinity. A single thing, a single life. The problem is that we are, and are about not to be.” That sentence alone captures the existential weight of his practice.

But there was no despair in Opalka’s tone, only clarity. He described painting numbers as a form of meditation. It was not repetitive, he said, but cumulative. He wasn’t painting the same thing; he was building something that could never be completed. Each number was a step further along a path with no end.

And yet, the impossibility of completion was precisely the point. Infinity not as a destination but as a process. Opalka was aligning his life with it. Accepting that the work would only end when he did.

The last number 5,607,249

He died in 2011 in Italy, having reached the number 5,607,249. By then, his canvases were pure white, the numbers barely discernible from the background. Silence, visually embodied, time has now officially stopped.

Today, Opalka’s works are held in major collections around the world, from the Centre Pompidou in Paris to MoMA in New York. But they are best experienced not as isolated paintings but in sequence, where the full scale and impact of the work comes into focus. The early black canvases throb with the stark contrast of beginnings. The mid-period greys murmur of the middle years, and the final white paintings shimmer with the near-vanishing.

Repetition as liberation

It’s melancholic and beautiful at the same time to see the artworks en masse. It feels less like visiting an exhibition and more like entering a temple of life. Opalka’s life offers something rare: a model of devotion without fireworks nor glitters. There were no sudden turns of style to please markets or critics. He “just” stayed the course. Repetition, for him, wasn’t limitation but instead it was liberation.

We live in an age addicted to newness, to the shock of novelty and the many fast trends. In that context, Opalka’s work is radical. To do one thing, well, for a lifetime? That’s a rebellion to me. There’s a story often told about him. Near the end of his life, someone asked if he feared death. He replied that he didn’t. He had, after all, been preparing for it every day. And maybe that’s what his art ultimately teaches: not how to defy time, but how to live within it. How to mark it with care. How to witness it pass, number by number, until the final breath.

So if you ever stand before a canvas by Roman Opalka, look closely. Those fading numbers aren’t just paint. They’re his moments lived.