The kiss in my living room: growing up with Robert Doisneau

As a kid, I grew up with a huge print of Robert Doisneau’s photograph, “Le Baiser de l’Hôtel de Ville,” hanging in our living room. I didn’t give it much thought; it was simply part of the family house decor. It wasn’t until years later that I discovered the story behind it, which turned out to be less romantic than I’d imagined. Today, I’d like to share a glimpse into the life of Robert Doisneau, iconic photographer, who roamed the streets of Paris, capturing the ever-changing world around him and his iconic image of romance.

The backstory of “Le Baiser de l’Hôtel de Ville”

As I mentioned earlier, the story behind this iconic image isn’t quite as romantic as it seems. Robert Doisneau was actually commissioned by Life magazine to capture a series on the lovebirds of post-war Paris. After the war, couples were springing up all over the city, creating a beautiful picture of joy and renewal. But the famous couple in his photograph weren’t those spontaneous lovers. While the French are known for their libertine attitudes, Doisneau’s camera still made them a bit uncomfortable. Plus, the rules around photographing strangers in the 1950s were much like they are today, getting permission was a must.

So, how did this now-legendary image come about? Doisneau use to hire actors to stage scenes for his photographs, and this time was no different. He enlisted two actors to pose as a couple, carefully crafting the perfect romantic moment. Then he filed it away. Didn’t even make much of it. The photo ended up sitting in his archives for nearly 30 years.

But in 1986, things took a turn. Victor Franck, a poster manufacturer, reached out to Doisneau looking for images to print. Doisneau was surprised by the request, but agreed and gave him permission to use that photograph for his posters. To him, it was just another nice shot, one among many taken for clients, not something he expected to become an international symbol of romance. It became a phenomenon. Suddenly, everyone wanted that kiss on their wall, including my parents. It was everywhere. A romantic fiction that, somehow, felt more truthful than a candid ever could.

A boy from Gentilly with a borrowed camera

Robert Doisneau wasn’t born into art galleries or long coats with Leica straps. He was a shy kid from Gentilly, a suburb just south of Paris. He lost his mother young and was pushed into learning lithographic engraving at only 13 years old, a dead-end trade even then. But everything changed when his half-brother handed him a camera. That moment? That was it. Suddenly, Doisneau discovered a new way to view the world around him. Gentilly, like much of France, was still dealing with the aftereffects of World War I, and even as a teenager, Doisneau instinctively documented the broken landscapes and visible poverty around him. His early photographs served as a visual diary of the town’s slow recovery.

At 20, he sold his first photo essay to Excelsior, covering the Saint-Ouen flea market. But life wasn’t ready to roll out the red carpet. The military came calling, and after his service, he spent the next five years documenting the gritty reality of assembly lines, workshops, and workers at Renault. He hated it. Always late. Always distracted. He got fired. Honestly? Thank God.

Because what followed was the beginning of his real life. The life of a man who saw the world in stills.

“Curiosity and disobedience are the two pillars of photography.”

– Robert Doisneau

Love, loss and a home studio in Montrouge

In 1936, he married Pierrette Chaumaison. They moved into a modest house in Montrouge, a place that became both a family home and his studio. They were partners in life and, often, in work. He photographed his daughters, his wife, their friends—sometimes because he couldn’t afford models, but more often because they were simply there. Real. Familiar. Loved.

Their marriage lasted over 50 years. Pierrette passed in ’93. Robert followed six months later, almost as if he couldn’t bear being apart. Today, their daughters still work from the same house, managing his archive with care. Although the atelier isn’t open to the public, its legacy lives on through their efforts.

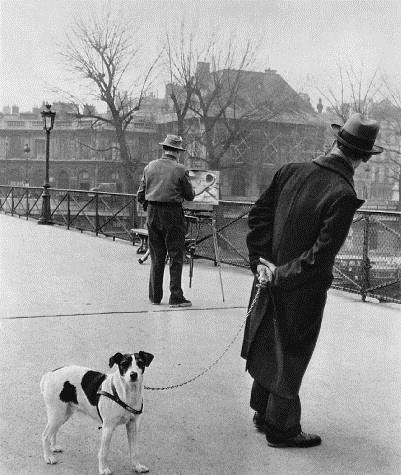

© Robert Doisneau / Atelier Robert Doisneau.

© Robert Doisneau / Atelier Robert Doisneau.

The occupation and liberation of France

During the Second World War, Doisneau returned to military duty, but only briefly. He ended up doing freelance work for government bodies to get by—but he was also part of the Resistance. Not with guns, but with forged papers and quiet acts of defiance. With just two rolls of film, he captured scenes of life under occupation and later, the fierce spirit of rebellion that fueled the city’s fight for freedom.

Belleville, Ménilmontant, the wild corners of Paris, he was there with his camera, documenting the uprising and the powerful emotions of Parisians reclaiming their city. These photographs are a testament to his courage and his remarkable ability to find beauty and defiance in even the darkest chapters of history.

The oldest photographic agency in France: Rapho

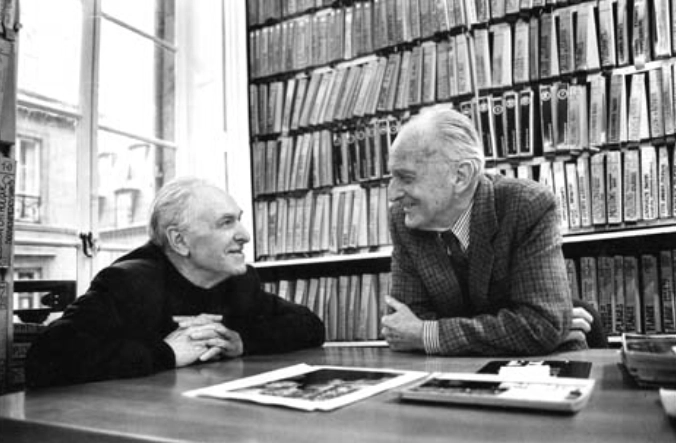

In 1946, just after World War II, Robert Doisneau joined the Rapho agency, the oldest photojournalism agency in France, founded in 1933. The agency’s director, Raymond Grosset, played a crucial role in shaping Doisneau’s career. Their relationship was more than just professional—Grosset supported and believed in Doisneau, helping him secure commissions and ensuring his work was seen by a global audience, with his images appearing in major publications worldwide.

Rapho gave Doisneau the creative freedom to pursue his true passion: capturing the beauty of everyday life in France, particularly in the streets of Paris. Whether it was a quiet moment in a café or the bustling energy of a market, Doisneau’s gift for portraying human connection blossomed under the agency’s guidance. Grosset’s unwavering belief in his talent, combined with Rapho’s reach, helped elevate Doisneau to legendary status as one of the most beloved photographers of the 20th century. Their partnership lasted for decades, and Rapho remained Doisneau’s professional home until his death in 1994, cementing his legacy as a master of capturing the human spirit.

© Elise Hardy / Rapho-Eyedea

The limited but vibrant colours of Robert Doisneau

Robert Doisneau is best known for his iconic black-and-white photographs that captured the everyday life and charm of post-war Paris. However, he did take a small number of colored photographs throughout his career, though they remain much less recognized. These images, while rare, offer a unique glimpse into Doisneau’s exploration of color photography. His approach to color was careful and understated, and unlike his black-and-white work, which often highlighted the contrasts and emotions of street life, his color photographs feel softer, almost painterly. While he didn’t focus heavily on color as a medium, the few examples we have reveal the same warmth and humanism that defines his entire body of work, providing a fresh perspective on the world he so famously captured.

Palm Springs in 1960 for Fortune magazine

In 1985, the DATAR (Inter-ministerial Delegation for Regional Planning and Attractiveness) launched the Photographic Mission: a huge order of photographs with the aim of “representing the French landscape of the 1980s”. Doisneau took part, casting a disenchanted and ironic look at these cities and neighborhoods, sometimes built in a hurry and subject to repeated crises since their creation.

The Parisian suburbs of the 80s for DATAR

In 1985, the DATAR (Inter-ministerial Delegation for Regional Planning and Attractiveness) launched the Photographic Mission: a huge order of photographs with the aim of “representing the French landscape of the 1980s”. Doisneau took part, casting a disenchanted and ironic look at these cities and neighborhoods, sometimes built in a hurry and subject to repeated crises since their creation. From squares and rectangles, rail lines (RER, trains) and motorways: Doisneau transcends the ugliness of the suburbs, extracts their architectural power, volume and social depths.

Conclusion

What I find most striking about Robert Doisneau’s photography is the genuine kindness and empathy he had for his subjects. Whether he was working on a job or just capturing a quick moment on the street, he always approached people with such care and respect.

There’s an enormous tenderness in his work. A belief that ordinary people are worth documenting. That life, even in its smallest gestures, deserves to be seen and remembered. No shock tactics. No heavy-handed symbolism. Just honesty, framed with affection. And maybe that’s why his work sticks with us, because it doesn’t shout, it hums.

If you ever get the chance to see his photographs in person, go. You won’t find a grand museum dedicated to him (not yet, anyway), but his exhibitions pop up often. Keep an eye out. And maybe, like me, you’ll find yourself standing in front of that kiss again, older now, knowing the truth, but loving it all the same.