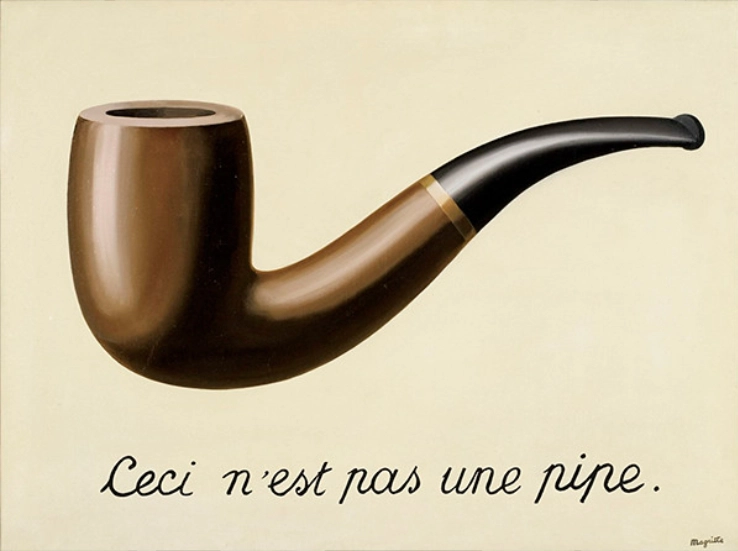

My love for René Magritte didn’t start in a museum or an art book. It began in my grandfather’s studio. He was the kind of man who quietly copied the masters, not to imitate, but to learn, to pay tribute, to add his own brushstrokes of mischief and meaning. Among his many inspirations, Magritte stood out. Even if you don’t think you’ve seen a Magritte, you probably have. His famous blue skies filled with clouds or the memorable pipe which isn’t a pipe are images we can find today all around the world.

The making of René Magritte

Before the bowler hats, before the riddles, René Magritte was just a kid who loved comics and cinema. Born in Belgium, he studied at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Brussels from 1916 to 1921, dipping his toes into Art Nouveau and Impressionism. But those movements didn’t quite scratch the itch. They were beautiful, yes, but he was looking for something else. Something that tugged at the corners of perception.

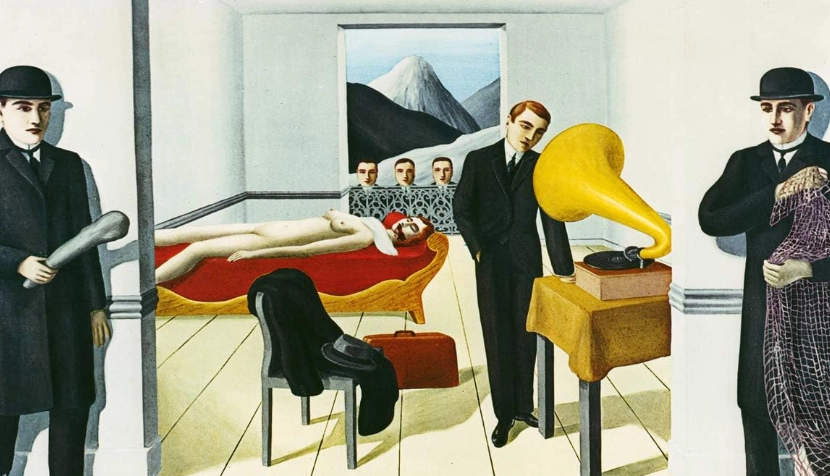

Then, everything changed. One day, Magritte saw Giorgio de Chirico’s Song of Love, and it hit him like a punch to the chest. It was surrealism before surrealism had a name. A rubber glove, a classical bust, an open sky, and somehow, it all made sense. That moment shook him. It rewired how he thought about art.

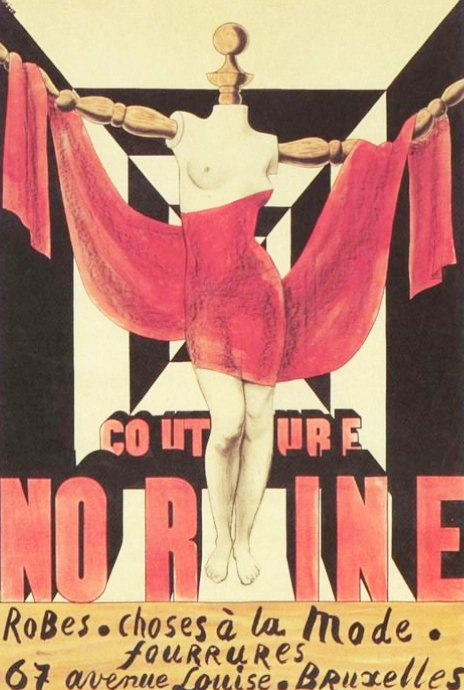

In the mid-1920s, Magritte found himself doing commercial work in Brussels—designing sheet music covers, posters, illustrations. It was clean, decorative, Art Deco. But he was already nudging against the frame. He was about to step into his own world.

His first exhibition in 1927 was bold, and largely ignored. Critics weren’t ready for his visual provocations. But he didn’t stop. He couldn’t.

Becoming Magritte

Between 1927 and 1930, Magritte lived on the outskirts of Paris and mingled with the surrealist crowd, Breton, Dalí, Miró. But he never quite fit the mould. He wasn’t seduced by dreams or drunk on subconscious automatism. He was a thinker. Meticulous. Controlled. Eventually, his rift with André Breton sent him back to Brussels, where he would remain for the rest of his life.

1935 marked a breakthrough. He produced work at an astonishing pace and exhibited in New York just two years later. In 1937, he spent a few intense weeks with British collector Edward James, resulting in some of his most iconic works: Reproduction Interdite, La jeunesse illustrée, Le Modèle Rouge. He was no longer just a Belgian curiosity. Magritte had arrived.

Seeing isn’t believing

Let’s talk about Reproduction Interdite. In it, a man (Edward James) stands before a mirror, but instead of seeing his face reflected, we see the back of his head. Twice. It’s quiet, it’s still, and completely unnerving.

Magritte wasn’t interested in tricking the eye. He wanted to unsettle the mind. The mirror, that everyday symbol of truth and clarity, is suddenly a liar. And the title, which translates to Not to Be Reproduced, adds yet another layer of irony. What is the role of art? Of reality? Of self-perception?

To Magritte, painting wasn’t a window to the soul or a portal to dreams, it was a puzzle. A quiet rebellion. He rejected the romanticised idea of art as emotion. Instead, he said, “The art of painting is the art of thinking.”

Thinking of images

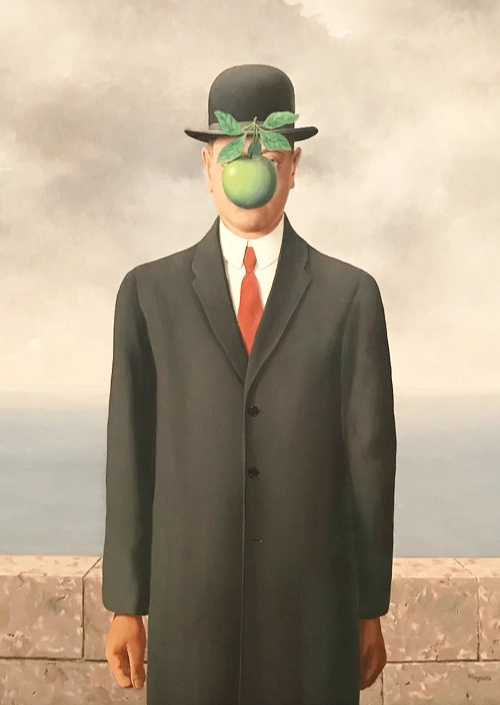

Unlike Dalí’s melting clocks or Max Ernst’s feverish hallucinations, Magritte’s world is neat, calm, almost too clean. But don’t be fooled. Beneath that surface lies a quiet chaos.

He didn’t paint dreams, he painted contradictions. He painted things exactly as they looked, but placed them in impossible contexts. An apple too big for a room. A train coming out of a fireplace. A woman’s body carved from wood. The logic of a dream wearing the clothes of reality. His brushstrokes were nearly invisible, no texture, no flourish. Just clarity. As if daring you to believe what you saw.

He questioned language (“This is not a pipe”), questioned identity, questioned the names we give to things. He severed image from meaning. He forced us to think. And in doing so, he made the ordinary feel deeply strange.

Where to see

If you want to truly immerse yourself in his world, the Musée Magritte Museum in Brussels is a must. It houses the largest collection of his works, over 230 pieces, sketches, photos, writings. The museum, which has garnered 8 nominations and prizes, attracts over 300,000 visitors annually from around the globe, offering a profound exploration of Magritte’s life and works. One that will leave you walking out a little slower, questioning the sky, the names of things, maybe even your own reflection.