Brutalism is unapologetic, a bit like dark art. These buildings don’t blend into the skyline; they stand out and make a statement. People strongly debate whether they improve or harm the look of a city, but one thing is for sure, they definitely grab attention. If you’ve ever come across a large, plain concrete building and felt like it had an imposing presence, it was likely Brutalist.

What is Brutalism, exactly?

Brutalism has nothing to do with violence, although you’d be forgiven for thinking so based on some of the architecture. The name actually comes from the French béton brut, meaning “raw concrete.” And raw is exactly what it is, visually and emotionally. Born in post-WWII Europe, Brutalism emerged as a rejection of ornament and superficial design. It prioritised utility, honesty, and materials in their most naked form.

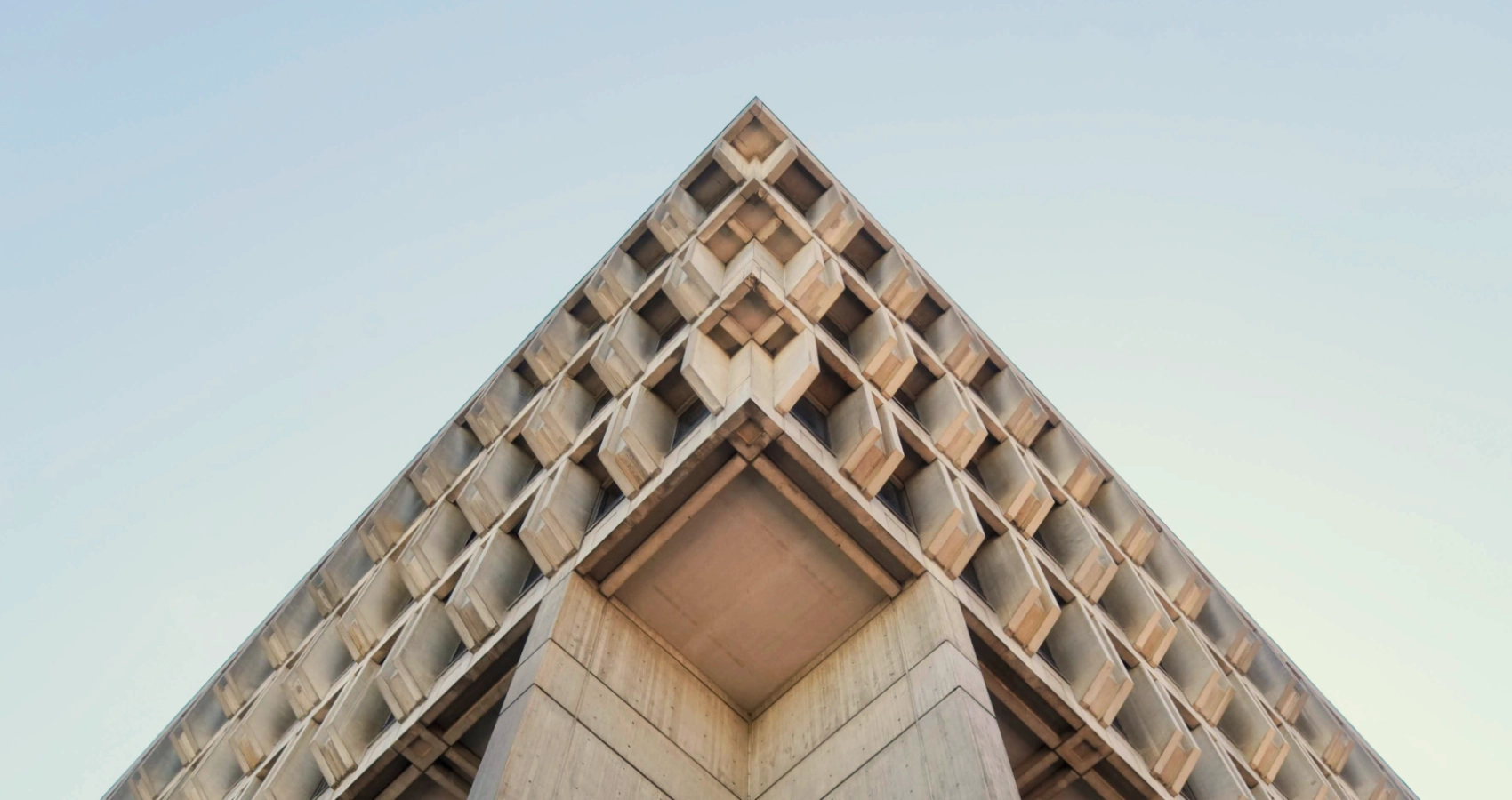

It’s heavy concrete, massive forms, repeated modular elements, and geometric lines that feel more sculptural than structural. These buildings were often government housing, libraries, universities, and civic centres, public buildings, designed with the intention of serving the masses.

The philosophy behind the concrete

Brutalism was a statement. It was a reaction to post-war reconstruction, to the need for fast, affordable housing and infrastructure. It was socialist at heart, democratic in intent. These buildings were meant to be shared, lived in, experienced by everyone, not just admired from afar.

And although the movement has been maligned as cold and oppressive, I sense that there’s an underestimated tenderness to Brutalism. There’s something deeply human about its attempt to come up with something honest, something unvarnished, despite the imperfections.

Barbican Estate, London

A labyrinth of raw concrete, elevated walkways, and bold lines, an entire ecosystem that feels both futuristic and ancient at once.

Boston City Hall, USA

Possibly one of the most debated Brutalist structures in America. Loved and loathed in equal measure, it’s a prime example of form following function, and then some.

The Church of John XXIII

Designed by Heinz Bienefeld, this sculptural concrete church sits on the edge of the University of Cologne campus. Its windowless facade feels like a medieval fortress at first glance, but step inside and you’re met with serene, sacred minimalism. Who knew you could use Brutalism to be spiritual?

Aula TU Delft, Netherlands

The Aula, by Jaap Bakema and Johannes van den Broek, is a geometric giant planted at the heart of the university. With its sharp concrete lines and sloping roof, it commands attention.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, The Hague, Netherlands

Also known as the “AZ Building,” this monolithic tower by architect Dick Apon once housed the Dutch Foreign Ministry which I used to pass frequently. With its rigid grid and commanding presence, it’s impossible to ignore.

The Ninth Fort in Kaunas, Lithuania

Part war memorial, part sculpture, the Ninth Fort monument by Alfonsas Vincentas Ambraziūnas is a fierce, fractured Brutalist masterpiece. Its jagged concrete forms rise like a frozen scream from the earth, commemorating the atrocities committed on the site during World War II.

Brutalism as a creative metaphor

If you’re a creative, you’ll identify with Brutalism’s emotional backbone. It’s in the truth, not in perfection or polished outcomes. Like an artist’s rough sketch, a raw demo or a first draft, Brutalist structures exposes the process. You can see the scaffolding in the design, the seams in the concrete. And that imperfection is what makes it so special.

In a way, Brutalism is what happens when you stop trying to please everyone and start telling the truth, about materials, about function, about people.

The love/hate divide

People either love Brutalism, defend it with passion, photograph it obsessively, or they loathe it, want it demolished, and call it an eyesore. There’s rarely any middle ground.

Why people hate it

Let’s start with the critiques, because there are plenty. Detractors often describe Brutalist buildings as:

- Cold, grey, and soulless

- Oppressive and intimidating

- Reminders of failed post-war urban planning

- “Ugly” or “depressing”

Some of this comes down to the material itself, bare concrete (especially when weathered) tends to stain, crack, or grow moss, giving a building a neglected, even dystopian look. Others tie it to emotion and memory. In places like the UK, former Eastern Bloc countries, and parts of Western Europe, Brutalism is often associated with failed housing projects, state bureaucracy, or even surveillance culture.

A 2009 YouGov survey provides insight into this divide. When presented with images of building designs, 77% of respondents preferred traditional architecture, while only 23% favored contemporary styles, which often encompass Brutalist elements. This suggests a significant leaning towards conventional architectural forms among the public.

Why people love it

And yet… Brutalism has a growing cult following. For its fans, Brutalism is raw honesty. It’s form as function, unvarnished. There’s a certain poetic melancholy in these concrete structures, a kind of stark romanticism that resonates, especially with creatives, designers, and younger generations who didn’t grow up under its shadow.

Despite historical preferences for traditional designs, Brutalism has experienced a resurgence in the digital era. Social media platforms, particularly Instagram, have played a pivotal role in this revival. As of March 2024, the hashtag #brutalism appeared in nearly 1.5 million posts, indicating a burgeoning interest in the style. This trend highlights a growing appreciation for Brutalist aesthetics among younger generations and digital communities.

So, what’s the deal? And what side are you on?

This love/hate split reveals more about us than it does about the buildings themselves. If you’re drawn to romanticism, nostalgia, or symbolism in design, you might find Brutalism deeply meaningful. If you prefer warmth, softness, or human-scale architecture, it might leave you cold. It’s one of the few movements where public perception is shaped as much by emotion and politics as it is by design. But maybe that’s why it matters. What side are you on?

Final thoughts

Brutalism isn’t for everyone, and that’s the point. It challenges, confronts, and sometimes even unsettles. But if you stand quietly in front of one of these structures and listen carefully, you might just hear the thoughts that came with this “movement” and appreciate it.

It’s a reminder that beauty doesn’t always come dressed in gloss and sparkles. Sometimes, it stands there in plain grey concrete, daring you to look deeper.