You might ask yourself why would I write an article about a silly children’s book? But this story has many unexpected layers. What appears to be a simple white bunny with two dots for eyes and a cross for a mouth, has roots and inspirations you probably didn’t know about. If you’ve wandered through Amsterdam’s galleries or spotted children’s books in Utrecht shop windows, you’ll recognise this character instantly. Nijntje, known globally as Miffy, represents far more than childhood nostalgia. She’s the unexpected intersection where Dutch modernism meets French avant-garde, where Mondrian’s rigid geometry softens into something a toddler can love.

Dick Bruna didn’t set out to create an icon. He just wanted to tell his son a bedtime story.

Growing up between books and bombs

Born on 23 August 1927 in Utrecht, Dick grew up in a world of books and creativity. His father was a publisher at A.W. Bruna & Zoon, a family business established in 1868. Dick’s mother, Johanna, was a joyful, resilient woman who filled their home with warmth, a quality Bruna often tried to recreate in his own stories. His childhood was comfortable, even luxurious, but it was shaped by the turbulence of the Second World War.

When the Nazis occupied the Netherlands, the Bruna family went into hiding. Instead of attending school, young Dick spent months drawing whatever he could see from their refuge. Designers from his father’s publishing house would occasionally visit, including Rein van Looy, who gave the boy sketching lessons. Those stolen hours became his art school.

After liberation, Dick’s father had plans for his son to learn his trade. He sent Dick to London first, then Paris. The internships were meant to prepare him for publishing, but Paris had other ideas. While working at Plon during the day, Dick spent evenings haunting galleries. Picasso impressed him. Léger fascinated him. But Matisse changed everything.

Those bold cut-outs, those impossible colour combinations that somehow worked perfectly inspired him. Matisse was seventy-something, confined to bed, yet creating art that pulsed with life. He’d sketch with charcoal on paper, then cut shapes from painted sheets, arranging them in compositions that made sense. Dick watched, absorbed, and understood something fundamental about the power of reduction.

Back in Utrecht, he briefly tried the Rijksakademie but left quickly. Formal training felt restrictive after what he’d witnessed in Paris. Better to learn by doing, by failing, by trying again, which is something I completely agree with.

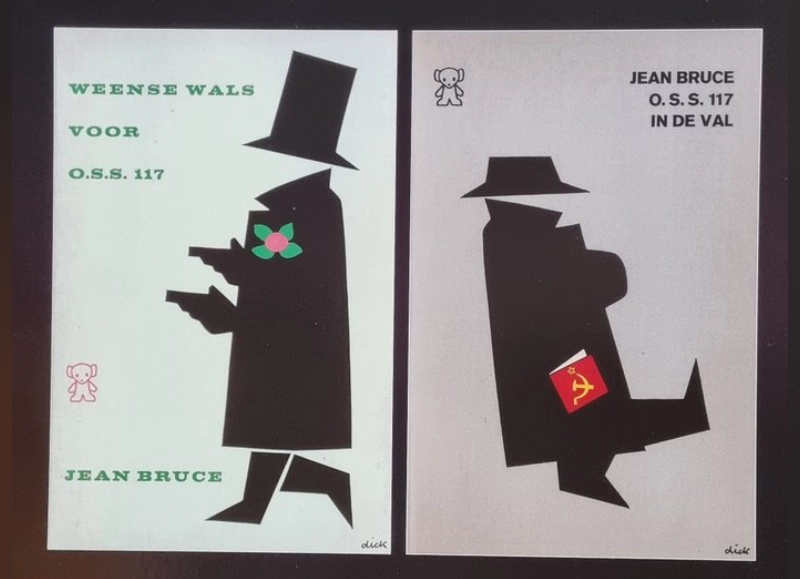

The publisher’s son finds his voice

Home meant responsibility, but also opportunity. Dick’s father needed him to prove himself capable of supporting a family, particularly since he’d fallen for the girl next door, Irene de Jongh. His courtship technique involved painting on his balcony, easel positioned for maximum visibility from her window. She thought him rather show-offy initially, but persistence paid off and together they raised three children.

So his father gave him a job as a graphic designer in his publishing house. Dick developed what would become his signature style: clean lines, primary colours, maximum clarity with minimum fuss. Over 2,000 covers taught him that simplicity sells, but more importantly, that simplicity communicates.

The birth of Miffy: a Dutch family story

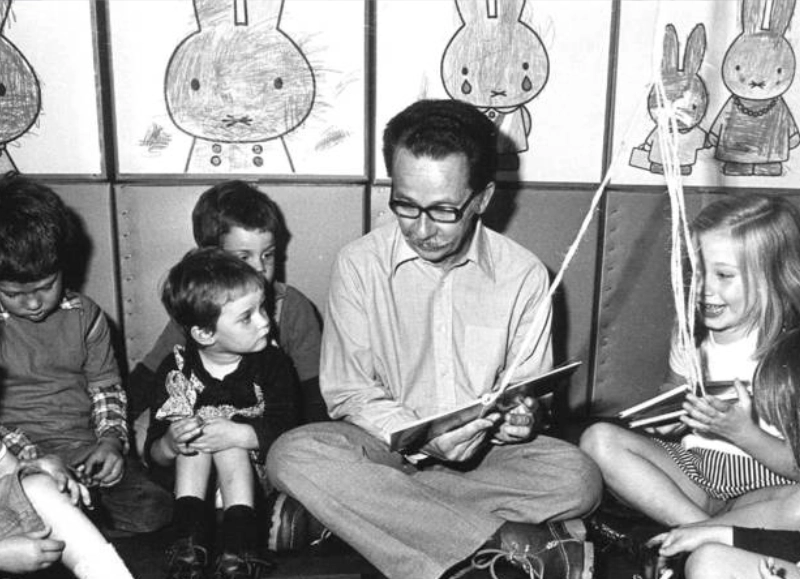

In 1955, during a family holiday on the Dutch coast, where a simple story about a rabbit became the start of something extraordinary. Dick Bruna had two sons, and for his youngest one, he would tell him stories every night about the rabbits hopping around their holiday house. After many stories, he thought: I should try to draw it. It turned out to be a very strange rabbit at first, but it was the beginning of everything. The first story was called “Miffy at Sea”.

The first sketches were odd, he’d later admit. Rabbits don’t naturally lend themselves to geometric simplification. But something clicked. Other children responded to these stories the same way his son did. Not just Dutch children, but kids everywhere loved Miffy.

“I never tried to teach children lessons, I just wanted it to be fun for them.” —Dick Bruna

Fun, but not simple to create. Each Miffy illustration required dozens of sketches. Dick would draw Nijntje again and again, removing everything unnecessary until only the essential remained. Think of Michelangelo claiming he simply freed David from the marble, except Dick was freeing a rabbit from visual noise.

The technique he’d absorbed from Matisse proved crucial. Thick black outlines first, painted with a brush. Then hand-cut coloured paper to fill the shapes, never paint. This process gave Miffy her distinctive flatness, her poster-like quality that works equally well in picture books and gallery walls.

De Stijl movement and Miffy

Understanding Miffy requires understanding the Netherlands itself. This is a country built on order imposed upon chaos, where the sea is held back by human engineering. The Dutch don’t trust romantic messiness; they prefer things structured, logical, purposeful. Probably why I liked living there so much.

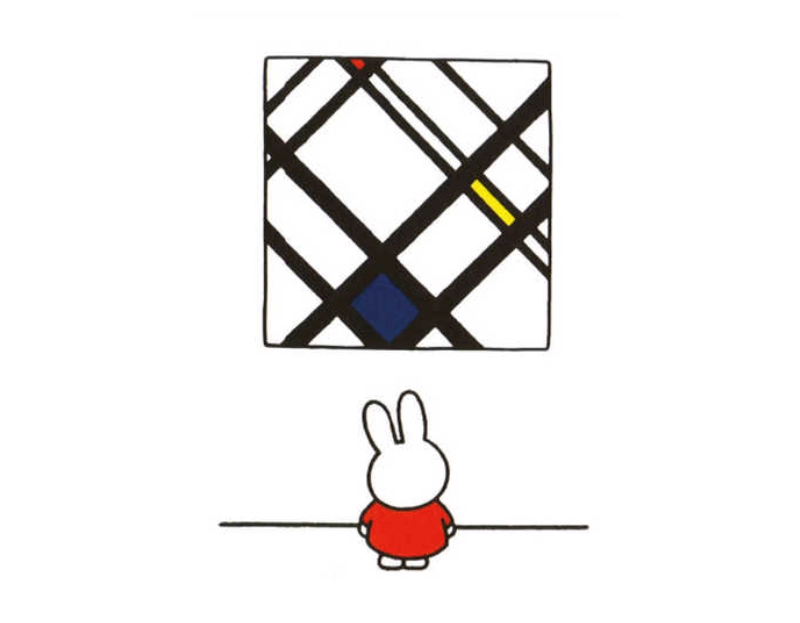

Miffy was born from the artistic expression of De Stijl movement, which was founded by Theo van Doesburg, and where Piet Mondrian became the face, alongside architect Gerrit Rietveld. Their mission in that era was radical simplification: strip art down to straight lines, rectangles, and pure colours. Red, blue, yellow, black, white. Nothing else permitted.

Mondrian believed chaos could be conquered through geometric harmony. His grids weren’t decorative; they were spiritual exercises, attempts to reveal universal order beneath surface confusion. Post-war Europe desperately needed such order, such clarity.

This philosophy seeped into Dutch design consciousness. The Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht also applied De Stijl principles to domestic architecture. Furniture followed. Graphic design adopted the aesthetic. By the time Dick Bruna started creating children’s books, geometric minimalism wasn’t avant-garde in the Netherlands, it was simply how things were done.

Matisse’s gift to Miffy

Yet Miffy isn’t cold like some Mondrian paintings can be. She radiates warmth, playfulness, joy. This comes from Dick’s other great influence: Henri Matisse’s late-career cut-outs.

By the 1940s, arthritis had made painting difficult for Matisse. So he invented a new medium: painted paper cut into shapes, arranged and rearranged until compositions sang. “I am drawing directly in colour,” he announced. The method gave him freedom to experiment with impossible colour relationships, purple next to orange, green alongside blue, combinations that shouldn’t work but absolutely did.

Dick adopted this technique. First, the black outline painted with brush strokes thick enough to be visible from across a room. Then, coloured paper cut to fit exactly within those boundaries. No paintbrush touching the colour areas, ever. This process ensured every hue remained pure, vibrant, unadulterated.

More importantly, Dick absorbed Matisse’s fearlessness about colour relationships. Traditional illustration taught that certain combinations clashed. Matisse proved traditional illustration wrong. If green and blue created the emotion you wanted, use green and blue.

The art of two dots and a cross

“With two dots and a little cross I have to make her happy, or just a little bit happy, a little bit cross or a little bit sad, and I do it over and over again. There is a moment when I think yes, now she is really sad. I must keep her like that.” —Dick Bruna

Dick’s description of creating Miffy’s expressions reveals something deep about minimalism. Reduction is removing details, but also about finding the precise detail that carries maximum emotional weight. Those dots and cross must work harder than any realistic portrait, conveying mood with microscopic adjustments.

Each Miffy book contains twelve or thirteen illustrations, never more. Dick would imagine the entire story first, then distill it into visual moments that could stand alone while advancing the narrative. Like haiku, every element must justify its existence.

The backgrounds stay white or single colours. No textures, no unnecessary objects, no visual clutter to distract from the emotional core. This is harder than it looks and is actually sophisticated restraint that leaves space for children’s imaginations to fill gaps.

Why Miffy still matters today

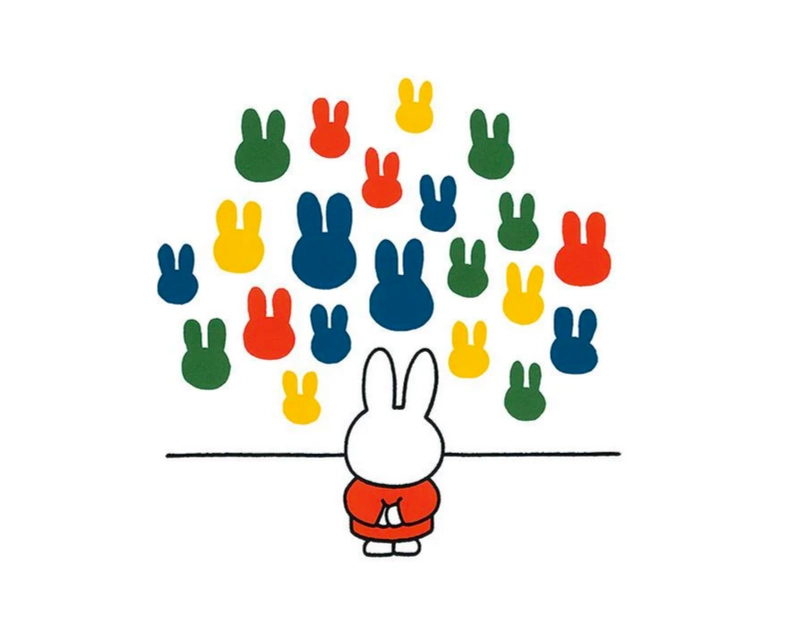

Miffy’s endurance, over seventy years and counting, suggests something important about visual communication in our cluttered age. While screens overflow with information and advertisements scream for attention, a simple white rabbit continues capturing hearts worldwide.

Museums recognise this significance. The Rijksmuseum has displayed Dick’s work alongside Mondrian and Matisse, making explicit the artistic lineage many sensed but couldn’t articulate. Fashion designers create Miffy collections that reference Mondrian’s compositions. Gallery shows explore how children’s illustration connects to fine art traditions.

But perhaps the real test isn’t critical acceptance, it’s that children still respond to Miffy the same way they did in 1955. In an era of computer animation and interactive media, hand-cut paper shapes still speak directly to young imaginations.

Keep it simple, stupid (KISS)

“It’s the most difficult thing to keep it as simple as possible,” Dick once observed. He succeeded where many fail because he understood that simplicity is clarity achieved through ruthless editing.

Miffy represents the synthesis of two major 20th-century art movements: De Stijl’s geometric order and Matisse’s expressive colour freedom. In Dick’s hands, these influences created something neither movement achieved alone, art that speaks universally while remaining extremely personal.

Next time you encounter Miffy, whether in a bookshop or gallery, remember you’re looking at more than charming children’s illustration. You’re seeing the legacy of Dutch modernism filtered through French avant-garde technique, refined into pure visual communication that works across cultures and generations! Yes, all that.

That simple white bunny carries within her the DNA of art history’s boldest experiments. She’s proof that the most radical gesture sometimes involves taking everything away until only love remains. So if you find yourself in The Netherlands, go visit the Nijntje Museum and enjoy all her history.

Wow, I loved reading this background story on Miffy/ Nijntje! I never really thought about the art influences on and broader meaning of Dick Bruna’s work. Very illuminating and very well written!